In this article I'm going to turn my attention to an area of the body I've been trying to develop more of an awareness of for quite some years – the pelvic floor (which I have written about before).

The pelvic floor is a multi-layered sheet of muscle and fascia that functions like a hammock at the bottom of your torso. The weight of your organs rest on it and in doing so it helps to maintain optimal intra-abdominal pressure. The muscles work to help maintain continence, and stabilise the hips and the whole spine-leg connection. Once it would've also lifted and wagged your tail! It's also the location of your muladhara chakra.

Over the last year I've been reading and digesting the book "Pelvic Power" by Eric Franklin. It's a very good little book. Franklin specialises in using visualisation to help your awareness and functional coordination of your body, which is great and makes it kinda fun! But as far as I can work out there are a couple of mistakes in his diagrams and I've been left feeling a little confused as to exactly what's what.

No surprise really since the pelvic floor is actually a very complex area!

Bones

Let's start with the bones to get our bearings. Here's an image of your pelvis from the front. If you can feel your hips sticking just underneath your waist, they're your Iliac Crests. The two protrusions sticking down underneath your bum are your Ischial Tuberosities (commonly known as your sitting bones). The two halves of your Ilium come together at the front at the Pubic Symphysis – commonly known as your pubic bone.

|

| Credit: Pearson Education, Inc (2015) |

That seems relatively straightforward...

Take a moment to identify the four "corners" of your pelvic floor with your fingers: your pubic bone at the front and your tail bone (coccyx) at the back, and the two sitting bones (ischial tuberosities) underneath. Actually touching these points really helps in getting a sense of where we're at in the body.

Muscles

From now on we have to be careful as there are some differences between the male and female anatomy. I think this is what has confused me for so long, as the books and sources I've read often show what it's like for a woman and don't say how it's different for a man...

(1) The deep layer

So let's start by looking down on the pelvic floor (as per this beautiful image of the female anatomy from BandhaYoga.com). There are three main muscles here: the pubococcygeus and the iliococcygeus (which, together with the puborectalis are collectively called the levator ani – literally "anus-lifter") and the coccygeus.

|

| Credit: BandhaYoga.com |

The Pubococcygeus forms the the top layer and connects front to back – tail to pubic bone. To engage this one, visualise drawing your coccyx and pubic bones towards each other. You might even feel some movement in your coccyx as you do this (you're wagging your tail!).

In men, contracting the Pubococcygeus muscle (and/or the abdominal muscles) can voluntarily engage the Cremaster muscle to lift the testicles. Normally the Cremaster is under involuntary control.

The Iliococcygeus and Coccygeus sit underneath and connect the tail bone to the sides of the ilium (a touch back from the pubic bone). The fibres of these muscles form a triangle (or fan) with the apex at the tail bone.

|

| The levator ani muscles can be thought of as a fan radiating out from the coccyx. Engaging and releasing these muscles shorten or lengthen the distance between the hips and the coccyx (putting your tail between your legs). Credit: Eric Franklin |

The puborectalis forms a sling around the rectum helping you hold things in when you need to... Squatting when you poo helps relax this muscle and eases the exit channel.

(2) The mid layer

Moving outwards, the next layer is the Urogenital Diaphragm. This is composed of the Deep Transverse Perineal muscle and the Urethral Sphincter (a ring muscle around the urethra – what you wee through).

The word perineum usually refers to the part of the pelvic floor between the anus and vagina/scrotum. The deep transverse perineal muscle sits under the levator ani muscle group and connects side-to-side (sitting bone to sitting bone). It's function is to help support the perineal body (central tendon running north-south along the perineum), the expulsion of semen in males, and squeezing the last drops of urine out for both sexes. To engage it, visualise pulling your sitting bones towards each other. This might take a bit of practice (you can tell when someone is trying by the look on their face...)

This image shows this mid-layer for both the male and female anatomy and how they correspond.

|

| Credit: Antranik |

(3) The superficial layer

For this layer it's helpful to look from underneath. As I'm sure you realise, the pelvic diaphragm has a number of holes in it... At the back we have the anus (surrounded by the deep levator ani muscles). At the front we have the urethra (and vagina for women) surrounded by the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles. In men, the bulbospongiosus surrounds the base of the penis and is the big spongy muscle you can feel running front-to-back along your undercarriage. It helps hold an erection and also helps ejaculation. In women, it contributes to clitoral erection, and closes the vagina. For both sexes it contributes to the contractions of orgasm, and also squeezing those last drops of urine out.

|

| Credit: Wikimedia Commons |

There's also the Superficial Transverse Perineal muscles which are narrow muscular strips connecting sitting bone to the central tendon on either side. In some people they may be absent or connect slightly differently.

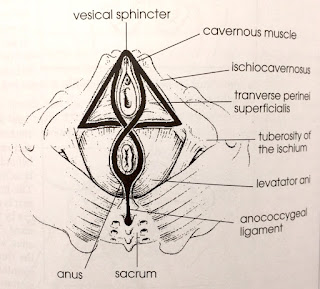

Here's another diagram from Fraklin's book showing the geometry of these muscles on the bottom surface of your pelvic floor (note: diagram is of a female anatomy). There's the triangle at the front formed of the Ischiocavernosus and Transverse Perineal muscles, then the figure of 8 formed by the Bulbospongiosus and anal sphincter. With these shapes, Franklin does a good job in simplifying things to help you work out what's what.

|

| Credit: Eric Franklin |

I'd like to finish by noting that these layers of muscle are (of course) all wrapped in fascia, forming the whole connected integrated (and complicated) pelvic diaphragm.

| I am a member of the Zenways sangha led by Zen master Daizan Skinner Roshi, and I teach meditation, mindfulness and yoga at the ZenYoga studio in Camberwell, London. See my website for further details. |

I'd love to hear from youLeave a comment below, I'd love to hear your thoughts. | |

Pass it onEnjoyed this post? Then please tweet it, share it on Facebook or send it to friends via e-mail using the buttons below. | |